2969 words, 15 minute read.

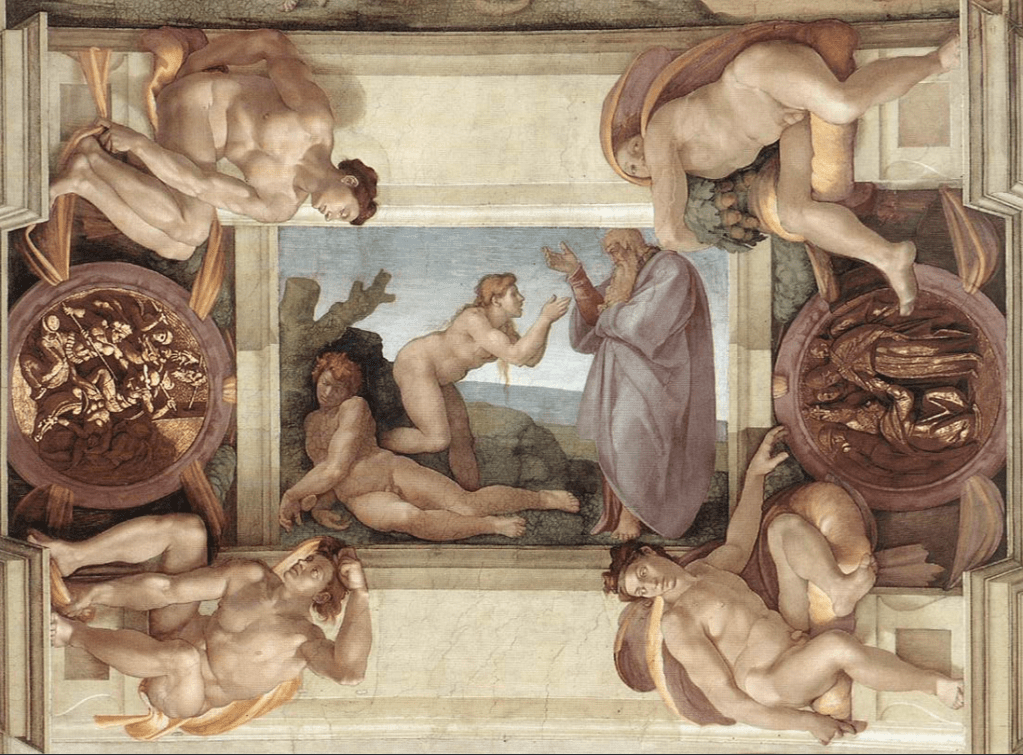

As I read, and recently wrote about, Judith Butler’s “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity”, my mind kept turning to memories of John Paul II’s Theology of the Body (“Man and Woman He Created Them”). I kept noticing parallels, not in where these two thinkers were going, but in patterns of relationships among concepts and in the clear desire of both to get to the bottom of the questions they posed. Since I read “Man and Woman He Created Them” eight years ago1, I wanted to go back to it and, this time, focus on who it is that John Paul II speaks about, more so than what he says about them. Who are the “man and woman”, the “male and female” he writes about and what is the locus in which he writes about them.

Before proceeding with a reading of the key passages from John Paul II’s writings, please, bear with me while I go into a serious issue with its English translation. Given the question at hand, the choice of vocabulary used to refer to human beings as distinct from male and female human beings needs to be examined. Key here is the fact that the origin of these texts, many of which were written before John Paul II’s election as pope, is Polish. In Polish, the noun “człowiek” refers to a human being with no indication as to their sex or gender, while “mężczyzną” indicates a male human and “niewiastą” a female one. However, since English does not have a noun to designate a human being without indicating their sex or gender, “człowiek” gets translated as “man”. The same happens when the German “Mensch” or the Hungarian “ember”, which are equivalent to the Polish “człowiek”, are rendered as “man” in English. John Paul II’s book is full of the word “man” in its English translation, while being full of the word “człowiek” in Polish. For this not to cloud our response to his words, I will replace “man” with “human being” (and italicize these substitutions and their grammatical consequences) in the following passages, where the Polish version has “człowiek”, and I would only use “man” if John Paul II used “mężczyzną”. Phrases like “the creation of man as male and female” become “the creation of the human being as male and female”, avoiding a masculinist slant that the English translation introduces and that is not present in the original.

From the outset, John Paul II makes it clear that he is concerned with the relationship between human beings and God, that his reflection has a theological and metaphysical character, and that it plays out both in the created, physical universe and beyond it in the uncreated, divine milieu (to borrow Teilhard de Chardin’s expression):

“The human person can neither be understood nor explained in their full depth with the categories taken from the “world,” that is, from the visible totality of bodies. Nevertheless, the human person too is a body.” […]

“Although the human person is so strictly tied to the visible world, nevertheless the biblical narrative does not speak of their likeness with the rest of creatures, but only with God (“God created the human being in his image; in the image of God he created them,” Gen 1:27).”

John Paul II also refers to objective reality when he points to the first source of knowledge about men and women in the context of the two accounts of their creation in Genesis. There the text of Genesis 1, which is historically more recent even though it appears earlier in the Hebrew Bible, presents a simultaneous creation of male and female humans:

“God created the human being in his image…; male and female he created them.” (Gen 1:27) One must recognize that the first account is concise, free from any trace of subjectivism: it contains only the objective fact and defines the objective reality, both when it speaks about the creation of the human being, male and female, in the image of God, and when it adds a little later the words of the first blessing, “God blessed them and said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, fill the earth, subdue it, and rule’” (Gen 1:28).

It is worth noting here that John Paul II’s references to “objective fact” are not an indication of some naïve literalist reading of Scripture. Instead, he speaks about how Genesis has a mythical character and what that means:

“Following contemporary philosophy of religion and of language, one can say that we are dealing with a mythical language. In this case, in fact, the term “myth” does not refer to fictitious-fabulous content, but simply to an archaic way of expressing a deeper content.”

The second Genesis account (which is historically more ancient) talks about a sequential process, where the human being is created first, before male and female are separated:

“[T]he characteristic feature of [the second creation account] is the separate creation of woman (see Gen 2:18–23), while the account of the creation of the first man (male) is found in Genesis 2:5–7. The Bible calls this first human being “human being,” (’āḏām), while from the moment of the creation of the first woman, it begins to call him “male,” îš, in relation to ’iššāh (“woman,” because she has been taken from the male = îš).

What is clear throughout the book is a view of the human being as male and female. It is a binary configuration though that is highly egalitarian with regard to the two “modes” or “incarnations” of being human. This also comes across clearly in the deeper analysis of the second Genesis account, where the female is created from the male while the male is asleep:

“[I]n the light of the context of Genesis 2:18–20, there is no doubt that the human being falls into this “torpor” with the desire of finding a being similar to himself. If by analogy with sleep we can speak here also of dream, we must say that this biblical archetype allows us to suppose as the content of this dream a “second I,” which is also personal and equally related to the situation of original solitude, that is, to that whole process of establishing human identity in relation to all living beings (animalia), inasmuch as it is a process of man’s “differentiation” from such surroundings. In this way, the circle of the human person’s solitude is broken, because the first “man” reawakens from his sleep as “male and female.”

The phrase “male and female” occurs 162 times in the text and is the default subject that John Paul II talks about here, as opposed to a different treatment of the two. As far as he is concerned, the overarching question is what God’s plan is for humans – male and female – in terms of their relationship with Him and among themselves.

While the focus is very much a binary view of human sexuality, John Paul II was not blind to it not being universal, to there being other states. This can be seen in the following passage where he refers to being male or female as the “normal constitution”. In this passage he also argues for the primacy of being a body over whether that body is male or female, of being humans before being men or women:

“Although in its normal constitution, the human body carries within itself the signs of sex and is by its nature male or female, the fact that the human being is a “body” belongs more deeply to the structure of the personal subject than the fact that in his somatic constitution he is also male or female. For this reason, the meaning of original solitude, which can be referred simply to “the human being,” is substantially prior to the meaning of original unity; the latter is based on masculinity and femininity, which are, as it were, two different “incarnations,” that is, two ways in which the same human being, created “in the image of God” (Gen 1:27), “is a body.””

Importantly, these two ways of being a body are not mapped discretely onto humans – i.e., these “ways” or “incarnations” are not exclusive at the level of an individual in John Paul II’s thought:

“In the mystery of creation—on the basis of the original and constitutive “solitude” of his being—the human being has been endowed with a deep unity between what is, humanly and through the body, male in them and what is, equally humanly and through the body, female in them.” […]

“Let us recall the passage of Genesis 2:23: “Then the human being2 said, ‘This time she is flesh from my flesh and bone from my bones. She will be called woman because from man has she been taken.’” In the light of this text we understand that the knowledge of the human being passes through masculinity and femininity, which are, as it were, two “incarnations” of the same metaphysical solitude before God and the world—two reciprocally completing ways of “being a body” and at the same time of being human—as two complementary dimensions of self-knowledge and self-determination and, at the same time, two complementary ways of being conscious of the meaning of the body.”

Important as these “ways” of being a body are, the true nature of humans, in John Paul II’s thought is their being in communion:

The human being becomes an image of God not so much in the moment of solitude as in the moment of communion. They are, in fact, “from the beginning” not only an image in which the solitude of one Person, who rules the world, mirrors itself, but also and essentially the image of an inscrutable divine communion of Persons.

Still reading Genesis, John Paul II argues that the heart of such communion, mirrored on the life of the Trinity, is the mutual self-giving of woman and man which takes place perfectly “before” the fall:

According to Genesis 2:25, “the man and the woman did not feel shame.” This allows us to reach the conclusion that the exchange of the gift, in which their whole humanity, soul and body, femininity and masculinity, participates, is realized by preserving the inner characteristic (that is, precisely innocence) of self-donation and of the acceptance of the other as a gift. These two functions of the mutual exchange are deeply connected in the whole process of the “gift of self”: giving and accepting the gift interpenetrate in such a way that the very act of giving becomes acceptance, and acceptance transforms itself into giving.”

Woman and man here are not the same, but have an equal essence, which is that of self-giving and receiving the other. The following passages show how John Paul II’s understand these two halves of the spousal relationship – i.e., the relationship that constitutes communion:

“[T]he woman, in giving herself (from the very first moment, in which, in the mystery of creation, she has been “given” by the Creator to the man), at the same time “discovers herself,” thanks to the fact that she has been accepted and welcomed and thanks to the way in which she has been received by the man. She therefore finds herself in her own gift of self […] when she has been accepted in the way in which the Creator willed her, namely, “for her own sake,” through her humanity and femininity; she comes to the innermost depth of her own person and to the full possession of herself when, in this acceptance, the whole dignity of the gift is ensured through the offer of what she is in the whole truth of her humanity and in the whole reality of her body and her sex, of her femininity. We add that this finding of oneself in one’s own gift becomes the source of a new gift of self that grows by the power of the inner disposition to the exchange of the gift and in the measure in which it encounters the same and even deeper acceptance and welcome as the fruit of an ever more intense consciousness of the gift itself.” […]

“While in the mystery of creation the woman is the one who is “given” to the man, he on his part, in receiving her as a gift in the full truth of her person and femininity, enriches her by this very reception, and, at the same time, he too is enriched in this reciprocal relationship. The man is enriched not only through her, who gives her own person and femininity to him, but also by his gift of self. The man’s act of self-donation, in answer to that of the woman, is for him himself an enrichment; in fact, it is here that the specific essence, as it were, of his masculinity is manifested, which, through the reality of the body and of its sex, reaches the innermost depth of “self-possession,” thanks to which he is able both to give himself and to receive the gift of the other. The man, therefore, not only accepts the gift, but at the same time is welcomed as a gift by the woman in the self-revelation of the inner spiritual essence of his masculinity together with the whole truth of his body and his sex. When he is accepted in this way, he is enriched by this acceptance and welcoming of the gift of his own masculinity. It follows that such an acceptance, in which the man finds himself through the “sincere gift of self,” becomes in him a source of a new and more profound enrichment of the woman with himself. The exchange is reciprocal, and the mutual effects of the “sincere gift” and of “finding oneself” reveal themselves and grow in that exchange.”

To complete this sketch of who John Paul II’s “man and woman” are, it is important to understand how he understands the consequences of the fall, of concupiscence (i.e., the “inclination to sin”) on the above relationships:

Concupiscence […] attacks precisely this “sincere gift”: it deprives the human being, one could say, of the dignity of the gift, which is expressed by their body through femininity and masculinity, and in some sense “depersonalizes” the human being, making them an object “for the other.” Instead of being “together with the other”—a subject in unity, or better, in the sacramental “unity of the body”—the human being becomes an object for the human being, the female for the male and vice versa.

By violating the dimension of the mutual gift of the man and the woman, concupiscence also casts doubt on the fact that each of them is willed by the Creator “for himself.” The subjectivity of the person gives way in some sense to the objectivity of the body. Because of the body, the human being becomes an object for the human being: the female for the male and vice versa. Concupiscence signifies, so to speak, that the personal relations of man and woman are one-sidedly and reductively tied to the body and to sex, in the sense that these relations become almost incapable of welcoming the reciprocal gift of the person. They neither contain nor treat femininity and masculinity according to the full dimension of personal subjectivity; they do not constitute the expression of communion, but remain one-sidedly determined “by sex.”

Concupiscence brings with it the loss of the interior freedom of the gift. The spousal meaning of the human body is linked exactly to this freedom. The human being can become a gift—that is, man and woman can exist in the relationship of the reciprocal gift of self—if each of them masters themselves. Concupiscence, which manifests itself as a “constraint ‘sui generis’ of the body,” limits and restricts self-mastery from within, and thereby in some sense makes the interior freedom of the gift impossible. At the same time, also the beauty that the human body possesses in its male and female appearance, as an expression of the spirit, is obscured. The body is left as an object of concupiscence and thus as a “terrain of appropriation” of the other human being. Concupiscence as such is not able to promote union as a communion of persons. By itself, it does not unite, but appropriates to itself. The relationship of the gift changes into a relationship of appropriation.

Expressed differently, an objectification of the other negates their being a subject and places power and ownership at the basis of relating to them, which ought to sound not unfamiliar to a feminist philosophical ear.

There would be a lot more to say about the rich theory of male and female human beings and their relationships that John Paul II sets out in his 400K word book, but I believe the above sketches out some of its key features. This theory is above all about how humans relate to God and to each other in a way that mirrors the inner life of God-Trinity. The men and women presented here are made in God’s image as a gift for each other, to be given freely and to be reciprocated. Made for each other, men and women are of equal status here, with perversions of such equality being the domain of failure and sin that are denounced and to be overcome. Wile being very much about two “ways of being a body” – male and female, John Paul II does not consider these to lead to facile and stereotypical distinctions, since both masculinity and femininity are present in all human beings.

1 I wrote a couple of articles back then, which can be found here: Man and woman: the beginning, Man and woman: a communion of persons, Man and Woman: Nakedness.

2 The original Hebrew here reads “’āḏām”, while what is left as “man” later in the quote is “îš” in the original.

One thought on “Men and women in John Paul II’s Theology of the Body”