1691 words, 8 min read

I have just come across a great talk by Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi on Jorge Luis Borges, given in Cordoba, Argentina last October in the context of the Courtyard of the Gentiles and his receiving an honorary doctorate from the Universidad Católica de Córdoba there. Ravasi gives some beautiful examples from Borges’ poetry that illustrate his approach to Scripture and Christ and where Ravasi underlines the richness of his understanding and the depth of his sincerity, which come from what Pope Francis speaks about as “periphery”. Note that the following is my translated transcript of the talk and that a more extensive version of it can be found here in Spanish.

To Borges, boundaries are always moveable and subtle. There is never an iron curtain between truth and fiction, between waking and dreaming, between reality and imagination, between rationality and feelings, between the essential and consequences, between concrete and abstract, between theology and fantasy literature, between Anglo-Saxon conjecture and Baroque emphasis.

Among his readings, an undisputed primacy was given to the Bible, as he had confessed: “I must remember my grandmother who knew the Bible off by heart, so I could enter literature along the way the Holy Spirit.” His paternal grandmother was in effect English and practicing Anglican and it was her who introduced the little Jorge Luis to the Scriptures and to the exalted English language. During a talk given at Harvard, dedicated to the art of storytelling, Borges, extolling the epic poem as the oldest form of poetry, lead to a triptych of masterpieces for humanity: “The Iliad, The Odyssey and a third ‘poem’ that stands out above the others: the four Gospels … The three stories of Troy, Odysseus and Jesus have been sufficient for humanity … Even though, in the case of the Gospels, there is a difference: I think that the story of Christ can not be told better.”

Let us now leave behind this specific topic of the literary and existential panorama of Borges to focus on a narrower scope that is particularly rich, so much so that here has exercised a small legion of scholars. Here we will deal with the aforementioned passion of the author for the Bible and we will do so through two examples.

The first is the story of Cain and Abel (Genesis 4:1-16) that had a poetic evocation in a short composition “The Unending Rose” entitled, as Borges often liked to do by revisiting Bible passages, “Genesis IV, 8”:

“In the first desert it was.

Two arms cast a great stone.

No cry. Blood.

For the first time death.

Was I Abel or Cain?”

Next to it we must, however, place the broadest reading of this Biblical scene in “In praise of Darkness” where the two brothers meet again after the death of Abel in an atmosphere of the eschatological court, even though the scene is set in the desert and the origins of the world. They sit, light a fire, while the day comes to an end and the stars, as yet unnamed, light up in the sky.

“By the light of the flame, Cain noticed the mark of a stone indented in Abel’s forehead and the bread he had raised to his lips fell before he could eat it and he asked whether his crime had been forgiven.

Abel answered:

“Did you kill me or did I kill you? I already cannot remember, and here we are, together like before.”

“Now, you must have forgiven me,” Cain said, “because to forget is to forgive. I will, too, try to forget.”

Abel replied softly:

“That’s right. While the remorse lasts, so does the guilt.””

Some have seen in this text a relativist moral conception by which an imperceptible transition is performed between good and evil, true and false, virtue and vice. Actually here we instead witness a process of transformation or alteration that we have indicated above and that Borges performs to show the infinite potentialities of an archetypal text. The same text allows continual re-transcriptions and in this case the aim is a paradigmatic celebration of forgiveness that makes the crime vanish completely: revenge is erased by forgetting and through it, the blame of the other becomes dissolved. What certainly remains always active is the fluidity of historical human reality and, therefore, of ethics that, in vain – in the eyes of Borges – also the “inspired” word tries to compress into defined and definitive certainties.

The second example is linked to the figure of Christ as Borges proposes in some of his many texts dedicated to this fundamental figure of Christianity.

“The black beard hangs down heavy over his chest.

His face is not the face from the engravings.

It’s harsh and Jewish. I do not see him

And will keep questing for him till the final

Day of my steps falling upon this earth.”

It was already in the twilight of his existence when Borges writes these verses of “Christ on the Cross”, dating them Kyoto 1984. They are verses of high spiritual tension, that all quote when they want to define Borges’ relationship with Christ, a hoped for encounter, but one that hasn’t occurred fully, bearing in mind that we don’t know his “last steps on earth”. Maria Lucrecia Romera wrote that “Borges confronts the tragic Christ of the Cross … and not the [theological] doctrine of the Resurrection .. His is not the optics of the believer’s faith, but that of the restlessness of the agnostic poet”. However, one needs to add immediately that the general observation made by the French writer Pierre Reverdy in his “En vrac” applies to certain of Borges’ verses: “There are fiercely harsh atheists who are much more interested in God than some frivolous and light believers”. Borges absolutely didn’t have “the fierce harshness” of an atheist, but his was certainly a more intense search than that of many pale and colorless believers. His restlessness was profound, hidden under the bark of a rhythmic dictation and streaked with disinterest, and even irony.

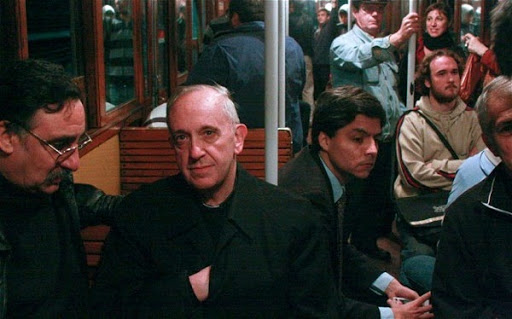

This is the intuition of Borges: the face of Christ is to be sought in the mirrors that reflect human faces. On the other hand, it was Jesus himself who said that everything done “to one of his least brothers”: hungry, thirsty, strangers, naked, sick and imprisoned, is done to him (Matthew 25:31-46). Behind the, often deformed, contours of human faces hides therefore the image of Christ and in this regard, the writer refers to St. Paul for whom “God is all in all” (1 Corinthians 15:28) . It is here, then, that we find Borges’s invitation to follow him in this human quest for Christ in the faces of men:

“We have lost those features,

just as a magic number made up of ordinary figures can be lost;

just as an image in a kaleidoscope is lost for ever. We may come across the features

and not know them. The profile of a Jew on an underground train

may be that of Christ; the hands that give us our

change over a counter may echo those that some soldiers

once nailed to the cross.

Perhaps some feature

of the crucified face lurks in every mirror; perhaps the face

died and was erased so that God could be everyone.”

[Paradise, XXXI: 108]

Now, on the basis of Borgesian Christology, we undoubtedly find the humanity of Jesus of Nazareth who is born, dies, even proclaims himself Son of God, and, therefore, assigns himself a transcendent quality. The writer does not ignore this interweaving of divine and human, of absolute and contingent, of eternal and time, of infinity and the limit and, even while witnessing the side of humanity, does not hesitate to interpret Christ’s consciousness in a poem of extraordinary power, as is that of the original Gospel matrix that generates it.

Here the title is, certainly, more explicit still: “John I, 14” (in “In praise of Darkness”). The verse is cut from the that literary and theological masterpiece that is the anthem-prologue of the Fourth Gospel: “The Lógos (Word) became sarx (flesh) and made his dwelling among us.” A verse that is a counterpoint to the solemn opening words of the hymn: “In the beginning was the Lógos, and the Lógos was with God, and the Lógos was God.” (1:1). Let us consider how John’s Lógos intrigued Goethe so much that in Faust he proposes a range of meanings to express its profound semantics: the Word is, certainly, Wort, word, but also Sinn, meaning, Kraft, power, and Tat, act, in line with the value of the parallel Hebrew word dabar, which means word and act/event. Let us read a few sentences from this surprising “autobiography” of the Word that is eternal (“Is, Was, Is to Come”), but is also “time in succession.”

“I who am the Was, the Is, and the Is to Come

again condescend to the written word

which is time in succession and no more than an emblem. …

I lived under a spell, imprisoned in a body,

in the humbleness of a soul. …

I knew wakefulness, sleep, and dreams,

ignorance, the flesh,

reason’s roundabout labyrinths,

the friendship of men,

the blind devotion of dogs.

I was loved, understood, praised, and hung from a cross.”

***

During the round-table discussion after his talk, Cardinal Ravasi then made a very significant gesture of appreciation towards Borges:

“Borges could be the best patron of the Courtyard of the Gentiles. Because he is not only in the courtyard of the gentiles, and he is not only in the courtyard of the believers. He was, instead, on top of that wall that divided the two spaces. That wall allowed for a good view both from one side and from the other. And Borges is a bit of a believer, in his own way as he said, and also a gentile. And it is because of this that the Courtyard of the Gentiles that takes place here in Córdoba or in Buenos Aires, in his hame, is the best Courtyard of the Gentiles.”

The patron [saint] of the Catholic Church’s dialogue with non-believers is an agnostic!