For several years now I have kept coming across articles by George Weigel, the US author and political and social activist, all of which have to my mind been misguided and lacking in insight. This undoubtedly makes me biased, which may be why I have not responded to his writings here before, and his latest piece – “The deeper issue at the Synod” – was destined to join that growing rank of articles to which I turned with silence. It is not like his latest feuilleton is any more objectionable than its predecessors, but, since it addresses a point that I do agree is pivotal for the upcoming Synod on the Family, and now that I have put my cards clearly on the table, I will spell out my disagreement in this case.

Weigel in this piece starts with recalling opposing positions before Paul VI issued Humanae Vitae, where the losers “argued, moral choices should be judged by a “proportional” calculation of intention, act, and consequence” while the winners – who upheld “tradition” – “held that some things were always and everywhere wrong, in and of themselves.” He then cites John Paul II’s Veritatis Splendor as reinforcing this position and moves on to recounting an analysis of the pre-Synod battle-lines by Prof. Thomas Stark, likely from this article – although without referring to it directly, where he argues that the real opposition at the Synod will be between two camps. The first, who, like Cardinal Walter Kasper, effectively believe that there are no “sacred givens”:

“Professor Stark argues that, for Kasper, the notion of what we might call “sacred givens” in theology has been displaced by the idea that our perceptions of truth are always conditioned by the flux of history – thus there really are no “sacred givens” to which the Church is accountable. To take a relevant example from last year’s Synod: on Kasper’s theory, the Lord Jesus’s teaching on the indissolubility of marriage, seemingly “given” in Scripture, should be “read” through the prism of the turbulent historical experience of the present, in which “marriage” is experienced in many different ways and a lot of Catholics get divorced.”

This, in Weigel’s reading of Stark results in Kasper denying human nature or there even being “Things As They Are”, since the attitude they attribute to Kasper is one where “what happens in history does not happen atop, so to speak, a firm foundation of Things As They Are; there are no Things As They Are.”

The second camp, instead believes that “the “truth of the Gospel” is a gift to the Church and the world from Jesus Christ: a “sacred given.”” Weigel then concludes that Kasper “absolutizes history to the point that it relativizes and ultimately demeans revelation – the “sacred givens” that are the permanent structure of Christian life.” The opposition, in Weigel’s view, is between an absolutization of history at the expense of relativizing revelation and tradition, versus a – in Weigel’s view – appropriate absolutization of the latter.

Instead of retracing Weigel’s steps through Stark’s article, which quotes from Kasper’s 1972 (!) book, An Introduction to Christian Faith, let me instead look at how well invoking John Paul II’s Veritatis Splendor as a rod for Kasper’s back holds up, and then proceed to argue for Weigel’s point being built on category mistakes.

Let’s begin by looking at Veritatis Splendor though, and test the strength of Weigel citing it as an argument for “sacred givens” and for “Things [Being] As They Are” as opposed to historical interpretation [I am sure St. John Paul II is slowly shaking his head in disbelief, looking down on this spectacle from the Father’s house.]

In Veritatis Splendor John Paul II kicks off with the following preamble:

“The splendour of truth shines forth in all the works of the Creator and, in a special way, in man, created in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gen 1:26). Truth enlightens man’s intelligence and shapes his freedom, leading him to know and love the Lord. Hence the Psalmist prays: “Let the light of your face shine on us, O Lord” (Ps 4:6).”

From the get go he speaks about a process: Truth leading to knowledge and love of God, rather than “givens” no matter how “sacred” they may be. Not a good start for the “Things As They Are” team.

Already in the second paragraph, John Paul II presents the teaching of the Church to be not words, but the Word – a person:

“Christ is “the way, and the truth, and the life” (Jn 14:6). Consequently the decisive answer to every one of man’s questions, his religious and moral questions in particular, is given by Jesus Christ, or rather is Jesus Christ himself.”

Then comes the killer (and we are still just in paragraph 2 of this 45K word gem of clear thinking by one of the 20th century’s greatest minds):

“The Church remains deeply conscious of her “duty in every age of examining the signs of the times and interpreting them in the light of the Gospel, so that she can offer in a manner appropriate to each generation replies to the continual human questionings on the meaning of this life and the life to come and on how they are related” (Gaudium et Spes, 4).”

Oh … “interpreting … in every age” … “manner appropriate to each generation” …

But, let’s take a closer look at how John Paul II thinks about permanence versus historicity, by reading the opening lines of §25:1

“Jesus’ conversation with the rich young man [Mt 19:16-21] continues, in a sense, in every period of history, including our own. The question: “Teacher, what good must I do to have eternal life?” arises in the heart of every individual, and it is Christ alone who is capable of giving the full and definitive answer. The Teacher who expounds God’s commandments, who invites others to follow him and gives the grace for a new life, is always present and at work in our midst, as he himself promised: “Lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Mt 28:20). Christ’s relevance for people of all times is shown forth in his body, which is the Church. For this reason the Lord promised his disciples the Holy Spirit, who would “bring to their remembrance” and teach them to understand his commandments (cf. Jn 14:26), and who would be the principle and constant source of a new life in the world (cf. Jn 3:5-8; Rom 8:1-13).”

Jesus, who is alive in His Church today, continues to converse with us and continues to supply us both with reminders of what He has already told us and with “new life” too through the Holy Spirit. Jesus’ words today are not mere mindless, mechanical repetitions of what he said 2000 years ago, but instead His continuing and evolving desire to lead us to an understanding and love of Himself, who is Truth, Goodness and Beauty.

To avoid giving a distorted impression about what John Paul II is saying here, it is important not to confuse the above process of renewal, of being up to date, of – as he himself later says – “doctrinal development” and “renewal of moral theology” (§28), with some giving in to the World. No, this being in the presence of the living Christ and under guidance from the Holy Spirit also means not to be “conformed to this world” (Rom 12:2):

“Assisted by the Holy Spirit who leads her into all the truth (cf. Jn 16:13), the Church has not ceased, nor can she ever cease, to contemplate the “mystery of the Word Incarnate”, in whom “light is shed on the mystery of man”. [… The Church needs to undertake] discernment capable of acknowledging what is legitimate, useful and of value in [contemporary tendencies], while at the same time pointing out their ambiguities, dangers and errors.”

John Paul II also speaks directly about how the divine and the human interplay in this context:

“The teaching of the Council emphasizes, on the one hand, the role of human reason in discovering and applying the moral law: the moral life calls for that creativity and originality typical of the person, the source and cause of his own deliberate acts. On the other hand, reason draws its own truth and authority from the eternal law, which is none other than divine wisdom itself. At the heart of the moral life we thus find the principle of a “rightful autonomy” of man, the personal subject of his actions. The moral law has its origin in God and always finds its source in him: at the same time, by virtue of natural reason, which derives from divine wisdom, it is a properly human law.”

Human reason discovers (imperfect historical process) divine wisdom (perfect atemporal). This leads us directly to the question of immutability that Weigel sees threatened by Kasper. Here John Paul II first insists on the reality of “permanent structural elements”:

“To call into question the permanent structural elements of man which are connected with his own bodily dimension would not only conflict with common experience, but would render meaningless Jesus’ reference to the “beginning”, precisely where the social and cultural context of the time had distorted the primordial meaning and the role of certain moral norms (cf. Mt 19:1-9). This is the reason why “the Church affirms that underlying so many changes there are some things which do not change and are ultimately founded upon Christ, who is the same yesterday and today and for ever”. Christ is the “Beginning” who, having taken on human nature, definitively illumines it in its constitutive elements and in its dynamism of charity towards God and neighbour.” (§53)

However, the very next lines distinguish the above, permanent structure from how it is expressed:

“Certainly there is a need to seek out and to discover the most adequate formulation for universal and permanent moral norms in the light of different cultural contexts, a formulation most capable of ceaselessly expressing their historical relevance, of making them understood and of authentically interpreting their truth. This truth of the moral law — like that of the “deposit of faith” — unfolds down the centuries: the norms expressing that truth remain valid in their substance, but must be specified and determined “eodem sensu eademque sententia” [“with the same meaning and the same judgment”] in the light of historical circumstances by the Church’s Magisterium.”

And John Paul II proceeds to refer to John XXIII’s words at the opening of the Second Vatican Council, saying that:

“This certain and unchanging teaching (i.e., Christian doctrine in its completeness), to which the faithful owe obedience, needs to be more deeply understood and set forth in a way adapted to the needs of our time.” (L’Osservatore Romano, October 12, 1962, p. 2.)

Looking back over St. John Paul II’s words and those of George Weigel, the funny aftertaste that the latter left in my mind crystalizes and, I believe, boils down to the following: a confusion of being with knowing and a mistaken assumption that attributes of the latter transfer to beliefs about the former. Weigel, taring with a broad brush, effortlessly transposes Kasper’s talking about a historicity of knowing (“perceptions of truth … conditioned … by history”) to an alleged historicity, or indeed total absence, of being (“there really are no “sacred givens””). This, even with a strained desire to apply the Principle of Charity, is a fundamental category mistake. Epistemological constraints do not ontological ones make.

Accepting an evolving, changing understanding and expression of Truth, as is consistent with John Paul II’s teaching, also has a corollary that may have irked Weigel, which is that past expressions and understanding have use-by dates and expiring validity in the present (without this implying a change of underlying reality). In one of the passages that Stark quotes from Kasper’s 1972 book, and identifies as a serious problem, Kasper expresses this situation as follows:

“Whoever believes that in Jesus Christ hope has been revealed for us and for all mankind, and whoever ventures on that basis to become in real terms a figure of hope for others, is a Christian. He holds in a fundamental sense the whole Christian faith, even though he does not consciously accept all the deductions which in the course of almost two thousand years the Church has made from this message.”

Yes, what was the best the Church could do to understand and express the Truth in the past may no longer be the best it can do today. And, just in case this interpretation of the renewal argument sounds dodgy or misguided, let’s hear it also from Pius XII, who has the following to say about his own teaching in view of his successors’ words, in his Mediator Dei:

“Clearly no sincere Catholic can refuse to accept the formulation of Christian doctrine more recently elaborated and proclaimed as dogmas by the Church, under the inspiration and guidance of the Holy Spirit with abundant fruit for souls, because it pleases him to hark back to the old formulas.”

“Old formulas” are no guarantee of holding on to “sacred givens,” whose expressions today need instead to be sought by living with the Jesus who walks among us today. A less obvious and easily testable answer to what doing the right thing means and one that requires courage, but one that leads to the Truth, however imperfectly we understand Her or adhere to Her.

1 Note that the italics in quotes from Veritatis Splendor are John Paul II’s own, who liked to use them for emphasis in all his writings.

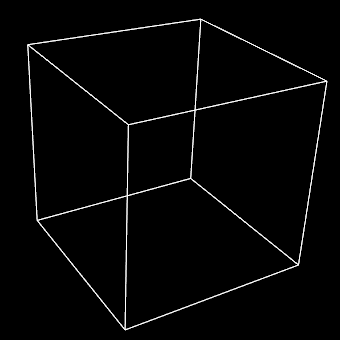

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment:

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment: