3749 words, 15 minute read.

Yesterday Pope Francis published his fourth encyclical letter, Dilexit nos, whose subject is the sacred heart of Jesus. It is concerned with the nature and consequences of God’s love, through the person of Jesus, for each one of us individually and collectively. Like all papal encyclicals, it is named after its opening words, which here come from St. Paul’s letter to the Romans (8:39). The Latin “dilexit nos” is rendered as “he loved us” in English. Seeing this opening phrase, I was struck by the use of the verb diligere instead of the perhaps more customary amare. Following up on its etymology showed that it comes either from dis- (“apart, asunder”) + legō (“to choose, to take”), or from dis- (“utterly, exceedingly”) + the Proto-Italic *legō (“to care”), with definitions of its meaning in English being “to esteem, prize, love, have regard, to delight in (something)” or “to set apart by choosing, to single (something) out, to distinguish (something) by selecting it from among others.” Already the first word of the encyclical therefore evokes a deep sense of closeness, tenderness and a heart on fire with personal, intense love, and the remaining 32K words were no less enriching and rewarding.

As usual, I would like to share my favorite passages from a first reading of the text, which I encourage you to read in full.

1. “HE LOVED US”, Saint Paul says of Christ (cf. Rom 8:37), in order to make us realize that nothing can ever “separate us” from that love (Rom 8:39). Paul could say this with certainty because Jesus himself had told his disciples, “I have loved you” (Jn 15:9, 12). Even now, the Lord says to us, “I have called you friends” (Jn 15:15). His open heart has gone before us and waits for us, unconditionally, asking only to offer us his love and friendship. For “he loved us first” (cf. 1 Jn 4:10). Because of Jesus, “we have come to know and believe in the love that God has for us” (1 Jn 4:16).

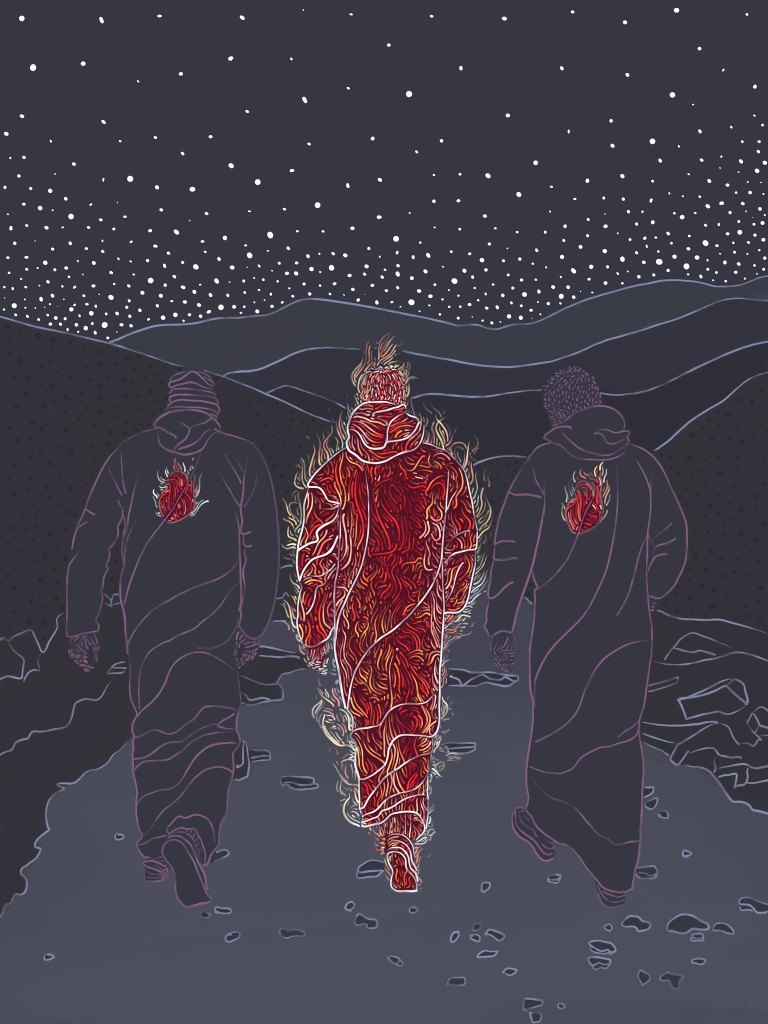

4. The disciples of Emmaus, on their mysterious journey in the company of the risen Christ, experienced a moment of anguish, confusion, despair and disappointment. Yet, beyond and in spite of this, something was happening deep within them: “Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking to us on the road?” (Lk 24:32).

5. The heart is also the locus of sincerity, where deceit and disguise have no place. It usually indicates our true intentions, what we really think, believe and desire, the “secrets” that we tell no one: in a word, the naked truth about ourselves. It is the part of us that is neither appearance or illusion, but is instead authentic, real, entirely “who we are”.

6. Mere appearances, dishonesty and deception harm and pervert the heart. Despite our every attempt to appear as something we are not, our heart is the ultimate judge, not of what we show or hide from others, but of who we truly are. It is the basis for any sound life project; nothing worthwhile can be undertaken apart from the heart. False appearances and untruths ultimately leave us empty-handed.

18. We see, then, that in the heart of each person there is a mysterious connection between self-knowledge and openness to others, between the encounter with one’s personal uniqueness and the willingness to give oneself to others. We become ourselves only to the extent that we acquire the ability to acknowledge others, while only those who can acknowledge and accept themselves are then able to encounter others.

19. The heart is also capable of unifying and harmonizing our personal history, which may seem hopelessly fragmented, yet is the place where everything can make sense. The Gospel tells us this in speaking of Our Lady, who saw things with the heart. She was able to dialogue with the things she experienced by pondering them in her heart, treasuring their memory and viewing them in a greater perspective. The best expression of how the heart thinks is found in the two passages in Saint Luke’s Gospel that speak to us of how Mary “treasured (synetérei) all these things and pondered (symbállousa) them in her heart” (cf. Lk2:19 and 51). The Greek verb symbállein, “ponder”, evokes the image of putting two things together (“symbols”) in one’s mind and reflecting on them, in a dialogue with oneself. In Luke 2:51, the verb used is dietérei, which has the sense of “keep”. What Mary “kept” was not only her memory of what she had seen and heard, but also those aspects of it that she did not yet understand; these nonetheless remained present and alive in her memory, waiting to be “put together” in her heart.

21. This profound core, present in every man and woman, is not that of the soul, but of the entire person in his or her unique psychosomatic identity. Everything finds its unity in the heart, which can be the dwelling-place of love in all its spiritual, psychic and even physical dimensions. In a word, if love reigns in our heart, we become, in a complete and luminous way, the persons we are meant to be, for every human being is created above all else for love. In the deepest fibre of our being, we were made to love and to be loved.

23. Whenever a person thinks, questions and reflects on his or her true identity, strives to understand the deeper questions of life and to seek God, or experiences the thrill of catching a glimpse of truth, it leads to the realization that our fulfilment as human beings is found in love. In loving, we sense that we come to know the purpose and goal of our existence in this world. Everything comes together in a state of coherence and harmony. It follows that, in contemplating the meaning of our lives, perhaps the most decisive question we can ask is, “Do I have a heart?”

28. It is only by starting from the heart that our communities will succeed in uniting and reconciling differing minds and wills, so that the Spirit can guide us in unity as brothers and sisters. Reconciliation and peace are also born of the heart. The heart of Christ is “ecstasy”, openness, gift and encounter. In that heart, we learn to relate to one another in wholesome and happy ways, and to build up in this world God’s kingdom of love and justice. Our hearts, united with the heart of Christ, are capable of working this social miracle.

34. The Gospel tells us that Jesus “came to his own” (cf. Jn 1:11). Those words refer to us, for the Lord does not treat us as strangers but as a possession that he watches over and cherishes. He treats us truly as “his own”. This does not mean that we are his slaves, something that he himself denies: “I do not call you servants” (Jn 15:15). Rather, it refers to the sense of mutual belonging typical of friends. Jesus came to meet us, bridging all distances; he became as close to us as the simplest, everyday realities of our lives. Indeed, he has another name, “Emmanuel”, which means “God with us”, God as part of our lives, God as living in our midst. The Son of God became incarnate and “emptied himself, taking the form of a slave” (Phil 2:7).

35. This becomes clear when we see Jesus at work. He seeks people out, approaches them, ever open to an encounter with them. We see it when he stops to converse with the Samaritan woman at the well where she went to draw water (cf. Jn 4:5-7). We see it when, in the darkness of night, he meets Nicodemus, who feared to be seen in his presence (cf. Jn 3:1-2). We marvel when he allows his feet to be washed by a prostitute (cf. Lk 7:36-50), when he says to the woman caught in adultery, “Neither do I condemn you” (Jn 8:11), or again when he chides the disciples for their indifference and quietly asks the blind man on the roadside, “What do you want me to do for you?” (Mk 10:51). Christ shows that God is closeness, compassion and tender love.

36. Whenever Jesus healed someone, he preferred to do it, not from a distance but in close proximity: “He stretched out his hand and touched him” ( Mt 8:3). “He touched her hand” ( Mt 8:15). “He touched their eyes” ( Mt 9:29). Once he even stopped to cure a deaf man with his own saliva (cf. Mk 7:33), as a mother would do, so that people would not think of him as removed from their lives. “The Lord knows the fine science of the caress. In his compassion, God does not love us with words; he comes forth to meet us and, by his closeness, he shows us the depth of his tender love”.

37. If we find it hard to trust others because we have been hurt by lies, injuries and disappointments, the Lord whispers in our ear: “Take heart, son!” (Mt 9:2), “Take heart, daughter!” (Mt9:22). He encourages us to overcome our fear and to realize that, with him at our side, we have nothing to lose. To Peter, in his fright, “Jesus immediately reached out his hand and caught him”, saying, “You of little faith, why did you doubt?” (Mt 14:31). Nor should you be afraid. Let him draw near and sit at your side. There may be many people we distrust, but not him. Do not hesitate because of your sins. Keep in mind that many sinners “came and sat with him” (Mt 9:10), yet Jesus was scandalized by none of them. It was the religious élite that complained and treated him as “a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners” (Mt 11:19). When the Pharisees criticized him for his closeness to people deemed base or sinful, Jesus replied, “I desire mercy, not sacrifice” (Mt 9:13).

38. That same Jesus is now waiting for you to give him the chance to bring light to your life, to raise you up and to fill you with his strength. Before his death, he assured his disciples, “I will not leave you orphaned; I am coming to you. In a little while the world will no longer see me, but you will see me” (Jn 14:18-19). Jesus always finds a way to be present in your life, so that you can encounter him.

44. Jesus’ words show that his holiness did not exclude deep emotions. On various occasions, he demonstrated a love that was both passionate and compassionate. He could be deeply moved and grieved, even to the point of shedding tears. It is clear that Jesus was not indifferent to the daily cares and concerns of people, such as their weariness or hunger: “I have compassion for this crowd… they have nothing to eat… they will faint on the way, and some of them have come from a great distance” (Mk 8:2-3).

45. The Gospel makes no secret of Jesus’ love for Jerusalem: “As he came near and saw the city, he wept over it” (Lk 19:41). He then voiced the deepest desire of his heart: “If you had only recognized on this day the things that make for peace” (Lk 19:42). The evangelists, while at times showing him in his power and glory, also portray his profound emotions in the face of death and the grief felt by his friends. Before recounting how Jesus, standing before the tomb of Lazarus, “began to weep” (Jn 11:35), the Gospel observes that, “Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus” (Jn 11:5) and that, seeing Mary and those who were with her weeping, “he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved” (Jn 11:33). The Gospel account leaves no doubt that his tears were genuine, the sign of inner turmoil. Nor do the Gospels attempt to conceal Jesus’ anguish over his impending violent death at the hands of those whom he had loved so greatly: he “began to be distressed and agitated” (Mk 14:33), even to the point of crying out, “I am deeply grieved, even to death” (Mk 14:34). This inner turmoil finds its most powerful expression in his cry from the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mk 15:34).

46. At first glance, all this may smack of pious sentimentalism. Yet it is supremely serious and of decisive importance, and finds its most sublime expression in Christ crucified. The cross is Jesus’ most eloquent word of love. A word that is not shallow, sentimental or merely edifying. It is love, sheer love. That is why Saint Paul, struggling to find the right words to describe his relationship with Christ, could speak of “the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal 2:20). This was Paul’s deepest conviction: the knowledge that he was loved. Christ’s self-offering on the cross became the driving force in Paul’s life, yet it only made sense to him because he knew that something even greater lay behind it: the fact that “he loved me”. At a time when many were seeking salvation, prosperity or security elsewhere, Paul, moved by the Spirit, was able to see farther and to marvel at the greatest and most essential thing of all: “Christ loved me”.

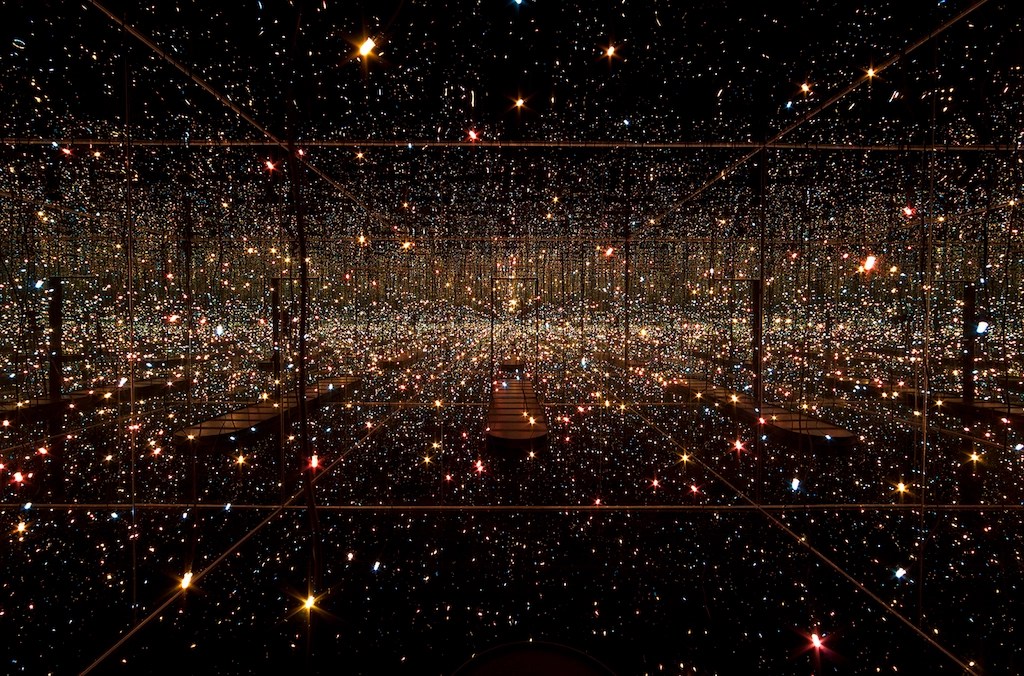

67. Entering into the heart of Christ, we feel loved by a human heart filled with affections and emotions like our own. Jesus’ human will freely choose to love us, and that spiritual love is flooded with grace and charity. When we plunge into the depths of his heart, we find ourselves overwhelmed by the immense glory of his infinite love as the eternal Son, which we can no longer separate from his human love. It is precisely in his human love, and not apart from it, that we encounter his divine love: we discover “the infinite in the finite”.

77. Our relationship with the heart of Christ is thus changed, thanks to the prompting of the Spirit who guides us to the Father, the source of life and the ultimate wellspring of grace. Christ does not expect us simply to remain in him. His love is “the revelation of the Father’s mercy”, and his desire is that, impelled by the Spirit welling up from his heart, we should ascend to the Father “with him and in him”. We give glory to the Father “through” Christ, “with” Christ, and “in” Christ. Saint John Paul II taught that, “the Saviour’s heart invites us to return to the Father’s love, which is the source of every authentic love”. This is precisely what the Holy Spirit, who comes to us through the heart of Christ, seeks to nurture in our hearts. For this reason, the liturgy, through the enlivening work of the Spirit, always addresses the Father from the risen heart of Christ.

161. In contemplating the heart of Christ and his self-surrender even to death, we ourselves find great consolation. The grief that we feel in our hearts gives way to complete trust and, in the end, what endures is gratitude, tenderness, peace; what endures is Christ’s love reigning in our lives. […] Our sufferings are joined to the suffering of Christ on the cross. If we believe that grace can bridge every distance, this means that Christ by his sufferings united himself to the sufferings of his disciples in every time and place. In this way, whenever we endure suffering, we can also experience the interior consolation of knowing that Christ suffers with us. In seeking to console him, we will find ourselves consoled.

162. At some point, however, in our contemplation, we should likewise hear the urgent plea of the Lord: “Comfort, comfort my people!” (Is 40:1). As Saint Paul tells us, God offers us consolation “so that we may be able to console those who are in any affliction, with the consolation by which we ourselves are consoled by God” (2 Cor 1:4).

167. We need once more to take up the word of God and to realize, in doing so, that our best response to the love of Christ’s heart is to love our brothers and sisters. There is no greater way for us to return love for love. The Scriptures make this patently clear:

“Just as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me” (Mt 25:40).

“For the whole law is summed up in a single commandment: ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself’” (Gal5:14).

“We know that we have passed from death to life because we love one another. Whoever does not love abides in death” (1 Jn 3:14).

“Those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen” (1 Jn4:20).

170. By associating with the lowest ranks of society (cf. Mt 25:31-46), “Jesus brought the great novelty of recognizing the dignity of every person, especially those who were considered ‘unworthy’. This new principle in human history – which emphasizes that individuals are even more ‘worthy’ of our respect and love when they are weak, scorned, or suffering, even to the point of losing the human ‘figure’ – has changed the face of the world. It has given life to institutions that take care of those who find themselves in disadvantaged conditions, such as abandoned infants, orphans, the elderly who are left without assistance, the mentally ill, people with incurable diseases or severe deformities, and those living on the streets”.

171. In contemplating the pierced heart of the Lord, who “took our infirmities and bore our diseases” ( Mt 8:17), we too are inspired to be more attentive to the sufferings and needs of others, and confirmed in our efforts to share in his work of liberation as instruments for the spread of his love. As we meditate on Christ’s self-offering for the sake of all, we are naturally led to ask why we too should not be ready to give our lives for others: “We know love by this, that he laid down his life for us – and that we ought to lay down our lives for one another” ( 1 Jn3:16).

205. The Christian message is attractive when experienced and expressed in its totality: not simply as a refuge for pious thoughts or an occasion for impressive ceremonies. What kind of worship would we give to Christ if we were to rest content with an individual relationship with him and show no interest in relieving the sufferings of others or helping them to live a better life? Would it please the heart that so loved us, if we were to bask in a private religious experience while ignoring its implications for the society in which we live? Let us be honest and accept the word of God in its fullness. On the other hand, our work as Christians for the betterment of society should not obscure its religious inspiration, for that, in the end, would be to seek less for our brothers and sisters than what God desires to give them.

211. Christ asks you never to be ashamed to tell others, with all due discretion and respect, about your friendship with him. He asks that you dare to tell others how good and beautiful it is that you found him. “Everyone who acknowledges me before others, I also will acknowledge before my Father in heaven” (Mt 10:32). For a heart that loves, this is not a duty but an irrepressible need: “Woe to me if I do not proclaim the Gospel!” (1 Cor 9:16). “Within me there is something like a burning fire shut up in my bones; I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot” (Jer 20:9).

215. Jesus is calling you and sending you forth to spread goodness in our world. His call is one of service, a summons to do good, perhaps as a physician, a mother, a teacher or a priest. Wherever you may be, you can hear his call and realize that he is sending you forth to carry out that mission. He himself told us, “I am sending you out” (Lk 10:3). It is part of our being friends with him. For this friendship to mature, however, it is up to you to let him send you forth on a mission in this world, and to carry it out confidently, generously, freely and fearlessly. If you stay trapped in your own comfort zone, you will never really find security; doubts and fears, sorrow and anxiety will always loom on the horizon. Those who do not carry out their mission on this earth will find not happiness, but disappointment. Never forget that Jesus is at your side at every step of the way. He will not cast you into the abyss, or leave you to your own devices. He will always be there to encourage and accompany you. He has promised, and he will do it: “For I am with you always, to the end of the age” (Mt 28:20).

218. In a world where everything is bought and sold, people’s sense of their worth appears increasingly to depend on what they can accumulate with the power of money. We are constantly being pushed to keep buying, consuming and distracting ourselves, held captive to a demeaning system that prevents us from looking beyond our immediate and petty needs. The love of Christ has no place in this perverse mechanism, yet only that love can set us free from a mad pursuit that no longer has room for a gratuitous love. Christ’s love can give a heart to our world and revive love wherever we think that the ability to love has been definitively lost.

219. The Church also needs that love, lest the love of Christ be replaced with outdated structures and concerns, excessive attachment to our own ideas and opinions, and fanaticism in any number of forms, which end up taking the place of the gratuitous love of God that liberates, enlivens, brings joy to the heart and builds communities. The wounded side of Christ continues to pour forth that stream which is never exhausted, never passes away, but offers itself time and time again to all those who wish to love as he did. For his love alone can bring about a new humanity.