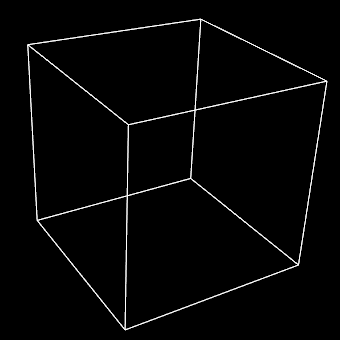

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment:

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment:

You are strapped into a chair, your head held firmly in place, and you see a bright, diffuse screen in front of you, showing a series of black lines. You notice that the screen can go from an only-just visible black point at its periphery, via lines cutting across it or forming triangles with its edges, to closed squares or even constellations of polygons moving and morphing across it. You also notice that there are several knobs and levers at your disposal and that you can influence the shapes seen on the screen. Your task is to work out how the patterns you see are formed.

All you have access to in this case is a sequence of experiences of a two-dimensional, bounded world, yet through painstaking experiments you come to the realization that what you are seeing is consistent with there being a wireframe cube behind the screen. All the patters, the changes from one pattern to another and the lengths of edges could be the result of a wireframe cube casting a shadow. Once you arrive at your conclusion you are released from your restraints and are free to exit the room. As you do so, another person exits the room next to you. A quick chat reveals you had the same experience, but it turns out that they are convinced that it was just a computer screen rather that the silhouette of a mesh cube. You enter each other’s rooms and realize that they look identical! You believe their room shows a 3D cube’s shadow; they believe your room contains a 2D computer-driven display. You both look for a way to access what is behind the respective screens and after a while you find the rooms backing onto your two ones. Your screen and theirs were indeed driven differently: one was a display driven by a computer and the other a piece of translucent plexiglass having a backlit cube cast shadows on it. Which was which remains a secret guarded by the two of you.

Now, my question to you: who was the more rational participant in this experiment? The person postulating a 3D entity on the basis of strictly 2D evidence or the person whose theories remained firmly 2D, in line with the nature of their evidence?

I would like to argue that they were both equally rational and that the distinction between them was not along rational-irrational lines and to underline the fact that they were both deriving their world views from the same evidence.

What was the point of this whole exercise though? It was to propose that empirical evidence alone is not sufficient to constrain explanation to a solely empirical domain (even just the use of mathematics in science, with its universal quantifier is beyond the empirical) and that the exact same experiences can be held up as a basis for alternative theories.

The last exegetical point I’d like to make though is that the two protagonists of the thought experiment can learn a lot from each other. The person hypothesizing the 3D cube can lend the other means for simplification while the strictly 2D person can share a more refined understanding of 2D relationships, which also enrich the cube’s understanding.

Why is it that I am concerned by the evidence-theory relationship and try to dig into its nature? It is because this is a key stumbling block in the rapprochement between atheist scientists and the rational religious. The former don’t get how the latter can transcend evidence while the latter are threatened by the former’s insights into empirical evidence. The many-to-many nature of the evidence-theory relationship also underlies inter-religious dialogue. Since the transcendent is infinite, hyper-dimensional and vastly exceeding the fragmentary insights we can have of it, also in terms of aspects we don’t even know about!, it is understandable that different interpretations of its actions have been formed in different cultures and by different people. It would be short-sighted to stop at an incompatibility between the monotheism of some religions, the personal Trinitarian insight of Christianity, the polytheism of Hinduism and the apparent atheism of Buddhism (in the strict sense of atheism as opposed to its current use as anti-theism) and arrive at the erroneous conclusion that these religions talk about different things rather than differently about aspects of the same (please, don’t mis-read this as me saying that everything that all religions claim is true, that all religions are equally true or that religions can be freely intertwined and recombined. End of caveat :).

If there is a God, who is infinite, transcendent and vastly more complex than us, wouldn’t his actions as experienced in our limited realm lead precisely to the variety of religions as well as agnosticism and atheism that we see today?

Just a quick hat-tip to Flatland, to the Chinese Room thought experiment and to the story of the blind men and an elephant (and surely to many others :).

A Navy SEAL (possibly previously involved in an operation closely watched by the POTUS himself) abseils from the ceiling of a small church, neutralizes and removes an old lady praying the rosary and disappears as quickly as she appeared. As commander of the unit, I judge the operation a success: mass is no time to pray the rosary. But, I am daydreaming …

A Navy SEAL (possibly previously involved in an operation closely watched by the POTUS himself) abseils from the ceiling of a small church, neutralizes and removes an old lady praying the rosary and disappears as quickly as she appeared. As commander of the unit, I judge the operation a success: mass is no time to pray the rosary. But, I am daydreaming …  Yesterday’s gospel reading was a bit of a puzzler and as I don’t think I ever heard it convincingly explained in a homily or made satisfactory sense of it myself, I started digging a bit into it. The text is from Matthew’s gospel (22:1-14) and presents the parable of the king’s son’s wedding feast where those who are invited refuse and the king’s servants bring in whomever they can find. The parable then ends in one of the guests being expelled for wearing the wrong gear plus there is a bit of killing too. Here is the full text:

Yesterday’s gospel reading was a bit of a puzzler and as I don’t think I ever heard it convincingly explained in a homily or made satisfactory sense of it myself, I started digging a bit into it. The text is from Matthew’s gospel (22:1-14) and presents the parable of the king’s son’s wedding feast where those who are invited refuse and the king’s servants bring in whomever they can find. The parable then ends in one of the guests being expelled for wearing the wrong gear plus there is a bit of killing too. Here is the full text: