I am feeling quite “meta” today and have no less than four reasons for it: first, what I am about to discuss is fundamentally meta, second, the act of writing about it to you is an instance of it, third, it ties several of the strands that I started in previous posts together, and, fourth, it has come to me in a way that illustrates the topic itself (thanks to my bestie, Margaret, of ‘the God of Explanations’ fame). If that is not enough to pique your interest, let me add that it is centered around a talk given by one of my favorite contemporary thinkers – Dr. Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The subject of the talk is an exploration of what it means to be human and revolves around the distinction between an individual and a person. In customary magisterial fashion, Archbishop Williams ties together the thinking of St. Augustine, Orthodox and Catholic theologians (Vladimir Lossky and Robert Spaemann), a Russian and a French philosopher (Mikhail Bakhtin and René Descartes), a French thinker (Alexis de Tocqueville), a psychotherapist (Patricia Gosling) and an LSE sociologist (Richard Sennett). The argument begins by claiming that the relevant polarity is not between individualism and communitarianism but between the concepts of an individual and a person.

Here an individual is simply an example of a certain thing: e.g., Bob is an example of a human being, just like Fido is an example of a dog. Seen from this “atomic” perspective (where, incidentally, “individuum” is merely the latinized version of the Greek “atomos”), the individual is the center of their own world – its solid core. Even when they engage in relationships with others, they always have “the liberty of hurrying back home,” and the best relationship they can have with the world, that is separate from them and beyond them, is control. The consequences of such a view of what it is to be human are alienation, non-cooperation and unease with limits. This view is summed up clearly by de Tocqueville saying that “[e]ach person, withdrawn into himself, behaves as though he is a stranger in the destiny of all the others.” It is also the psychological and anthropological parallel of the epistemic approach pioneered by Descartes (and driven to its limit in the “brain-in-a-vat” scenario), that I also adapted in an earlier post and that, in art, is mirrored by Antony Gormley’s approach to sculpture.

The other concept of a human being is that of a person, where there is “something about us as a whole that is not defined just by listing the facts that happen to be true about us” and where a person is a “subject [that is] irreducible to its nature” (Lossky). Williams argues though that while “we know what we mean by personal/impersonal and persons in relation, […] we struggle to pin down what we mean that we cannot be reduced just to our nature.” He then goes on to postulating that “what makes me a person and distinct from another person is not a bundle of facts, but relations to others. I stand in the middle of a network of relations.” This leads to the definition of a person as the “point at which relationships intersect.”

Williams then moves on to the question of how one is to determine whether another is a human person and, following from the previous analysis, concludes that this cannot be done on the basis of a checklist for whether a given set of pre-requisites are present. Instead, we need to “form a relation, converse, to determine whether another is a person” and that language helps us to decide. He is quick here to move from a narrow concept of language as verbal only to a broad one that includes gestures and the “flicker of an eyelid.” This means that “[p]ersonal dignity or worth is ascribed to human individuals because, in a relationship, each of us has a presence or meaning in someone else’s existence. We live in another’s life. Living in the life of another is an implication of the profound mysteriousness about personal reality. Otherwise you end up with the model where somebody decides who is going to count as human.” Such a test of human personhood based on relateability very much reminded me of Turing’s test of machine intelligence, where the basis again is not a predetermined set of criteria, but the ability for a machine to converse with (relate to) a human person and for that person to recognize the machine as a person. Williams’ point about “each of us [having] a presence or meaning in someone else’s existence” also brought back echoes of Martini’s “the other is within us.”

How does the individual (which is by far the position with the strongest epistemic justification) see themselves as a person though? Here Williams quotes the following passage from Spaemann:

“Each organism naturally develops a system that interacts with its environment. Each creature stands at the center of its own world. The world only discloses itself as that which can do something for us; something becomes meaningful in light of the interest we take in it. To see the other as other, to see myself as his “thou” over against him, to see myself as constituting an environment for other centers of being, thus stepping out of the center of my world, is an eccentric position. […] As human beings in relationship, we sense that our environment is created by a relation with other persons; we create an environment for them and in that exchange, that mutuality, we discover what person means.”

How do you “step out” and assume an “eccentric position” tough? Here, Williams admits that such “stepping beyond one’s own individuality requires acts of faith. Living as a person is a matter of faith.” And I completely agree with him – strictly from a position of introspective enquiry, from Gormley’s “darkness of the body,” there is no fact-based way out. There is a need for a Kierkegaardian “leap of faith,” but I would like to argue that it does not require a belief in God and in fact is akin to Eco’s communist acquaintance’s belief in the “continuity of life” discussed in an earlier post.

Finally, let’s also look at what Williams says about the aspect of personhood that is revealed as a consequence of belief in God:1

“Before personal relations, we are in relation with God. I am in relation to a non-worldly, non-historical attention which is God. My neighbor is always somebody who is in a relation with God, before they are in a relation with me. There is a very serious limit for me to make of my neighbor what I choose. They don’t belong to me and their relation to me is not what is true of them or even the most most important thing that is true of them. Human dignity – the unconditional requirement that we attend with reverence to one another – rests firmly on that conviction that the other is already related to something that isn’t me.”

In summary, a very clear picture emerges here, where I can think of myself as an individual – a world unto myself – or as the intersection of relations with others that allows me to go beyond myself and recognize in others that they are part of my world and I part of theirs. As a Christian this eccentricity also reveals to me that the relations I have with others build on the relations He has with them already and allow me to relate to Him not only in the intimacy of my self but also through my neighbors.

1 As an argument, this is essentially a variant of Bishop Berkeley’s response to the following challenge to his philosophy, where being is predicated on perceiving:

There was a young man who said God,

must find it exceedingly odd

when he finds that the tree

continues to be

when noone’s about in the Quad.

To which Berkeley responded with another limerick:

Dear Sir, your astonishment’s odd

I’m always about in the Quad

And that’s why the tree

continues to be

Since observed by, yours faithfully, God

:)))

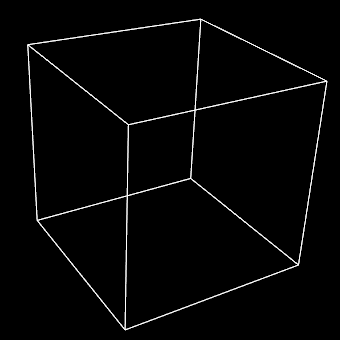

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment:

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment: