2191 words, 11 min read

Is the body subject to the mind, or the mind something that the body does? Is it my body that holds me – my true, immaterial self – back, or is it my parasitic mind that inhibits the freedom of my body, my true, physical self? Ought I to favor the purity of ideas over messy matter, or the concreteness of being over the ephemeral nature of the mind?

Such questions are the polar opposites of a concept of the human person as a single being that is at home both in the material world and in a world that – at least apparently – is beyond matter: a world of thought, memory, relationships and values.

In the context of Christianity, the above is an opposition between the dualist heresy that denigrates matter and the body and attributes goodness only to the soul, and the concept of differentiated unity pervading the New Testament and made explicit in St. Paul speaking of the “spiritual body” [soma pneumatikón] (1 Corinthians 15:44). In Karl Barth’s words, “man is an embodied soul, a besouled body” and the Catechism of the Catholic Church presents an ultimately Trinitarian anthropology: “[t]he unity of soul and body is so profound that one has to consider the soul to be the “form” of the body. [… S]pirit and matter, in man, are not two natures united, but rather their union forms a single nature.” (§365).

With that brief preamble in mind, let us turn to a program by the philosopher Roger Scruton where he speaks about beauty, a subject very close to my heart (in the Homerian sense). Instead of being enlightening or thought provoking, Scruton’s position lead me to disappointment and frustration and, eventually (after some hesitation, given the strength of my initial aversion) to the writing of this piece.

There is a lot to be “against” in this hour-long program, but I will focus on only three of its, liberally intermingled, aspects here: superficiality, internal inconsistency and dualism.

Before arguing in favor of his positions’ flaws, I would first like to underline the good that I have seen in Scruton’s thought. For a start, I wholeheartedly share his insistence on the importance of beauty:

“I want to persuade you that beauty matters; that it is not just a subjective thing, but a universal need of human beings. If we ignore this need we find ourselves in a spiritual desert. I want to show you the path out of that desert. It is a path that leads to home.”

Scruton also presents beauty in art as impelling its recipient towards the good – “The beautiful work of art brings consolation in sorrow and affirmation in joy.” – and as a gateway to profound truths: “The most ordinary event can be made into something beautiful by a painter who can see into the heart of things.” And Scruton also aligns himself with Immanuel Kant’s emphasis of selflessness in art:

“Kant argued that the experience of beauty comes when we put our interests to one side; when we look on things not to use them for our own purposes or to explain how they work or to satisfy some need or appetite, but simply to absorb them and to endorse what they are.”

Sadly that is all I can echo from Scruton’s 6300 word defense of beauty, since the rest strikes me as little more than an attempt to justify what is to his taste and belittle what isn’t, instead of being an attempted enquiry into beauty.

The first issue I find with Scruton’s thought is that there is a tremendous superficiality and lack of charity in his approach to post-nineteenth-century art. This is coupled with a blanket attribution of goodness to all that came before it, paired with a universal belittling of all that came since. Virtually at the start of the program, Scruton declares:

“[I]n the 20th century beauty stopped being important. Art increasingly aimed to disturb and to break moral taboos. It was not beauty but originality however achieved and at whatever moral cost that won the prizes. Not only has art made a cult of ugliness. Architecture too has become soul-less and sterile. […] One word is written large on all these ugly things and that word is “Me.” My profits, my desires, my pleasures. […] Our world has turned its back on beauty and because of that we find ourselves surrounded by ugliness and alienation.”

To my mind this is little more than an expression of Scruton’s esthetic response to contemporary art rather than the result of an analysis either of its motives (in which he assumes beauty not to feature) or of its beauty (which, incidentally, Scruton never defines or analyses beyond declaring its presence or absence). If Scruton had taken the trouble to listen to even just the responses of those who were interviewed in his own program (!), he could have seen that beauty is very much still a driving force in contemporary art. Admittedly not a beauty that he might recognize or appreciate, but beauty nonetheless and not the universally base consumerist pursuit of selfish pleasures that he attributes it.

The clearest example in the program is the following passage from Tracey Emin being interviewed by David Frost about her 1998 piece “My Bed”:

Frost: “[T]he Tate says that it is [beautiful]. But what do you want the viewer, the visitor to the gallery to say? Do you want…. You don’t want them to say, ‘I think that’s beautiful.’”

Emin: “No, no one’s actually said that, only me.”

Frost: “You think it’s beautiful?”

Emin: “Yeah…. I do, otherwise I wouldn’t have showed it.”

Far from beauty being absent from artistic expression, Emin here not only points to it as the motive of her work (“otherwise I wouldn’t have showed [sic] it”) but, to my mind, also expresses a sadness about its absence from the minds of those who view her work.

Another piece that Scruton presents as an example for the absence of beauty is Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 “Fountain” which, he argues “was [a] satirical [gesture], designed to mock the world of art and the snobberies that go with it.” In other words, Duchamp’s work is about mockery and is entirely disconnected from beauty. Interestingly, the Tate describes this work in different terms – as “testing the commitment of the new American Society to freedom of expression and its tolerance of new conceptions of art.” And, importantly, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, writing in a letter from 1917 describes his photograph of Duchamp’s work as “really quite a wonder – Everyone who has seen it thinks it beautiful – And it’s true – it is. It has an oriental look about it – a cross between a Buddha and a Veiled Woman.” Again, news of the death of beauty is greatly exaggerated …

Finally, let’s look at the words of a third of the enemies of beauty as presented by Scruton – the conceptual artist and painter Michael Craig-Martin. During his interview with Scruton, he responds to a question about what the point was of the changes that Duchamp wanted to usher in, by saying:

“I also think it is important to say that the notion of beauty has been extended to include things that would not have been thought of – that’s part of the artist’s function, to make one see something as beautiful that no one thought was beautiful until now.”

The difficulty here is not that Scruton does not like what Emin, Duchamp and Craig-Martin have done – he is free to experience reality as he pleases – but that he equates the lack of his perception of beauty in their work with their own disinterest in beauty and that he attributes motives to them that are base and among which beauty does not figure.

A second flawed strand in Scruton’s arguments is a total lack of self-consistency. E.g., he is quite content to launch into a tirade against today’s “people”:

“Maybe people have lost their faith in beauty because they have lost their belief in ideals. All there is, they are tempted to think, is the world of appetite. There are no values other than utilitarian ones. Something has a value if it has a use and what’s the use of beauty? […] Our consumer society puts usefulness first and beauty is no better than a side-effect.”

And, almost in the same breath put the following question to Craig-Martin, as a challenge to contemporary art: “What is the use of this art? What does it help people to do?” In other words: “Consumer society puts utility before beauty, and what’s the use of contemporary art anyway?!”

Scruton also simultaneously does two things: he bemoans a “cult of ugliness” at the beginning of the program and, half an hour later, states that art has always done that:

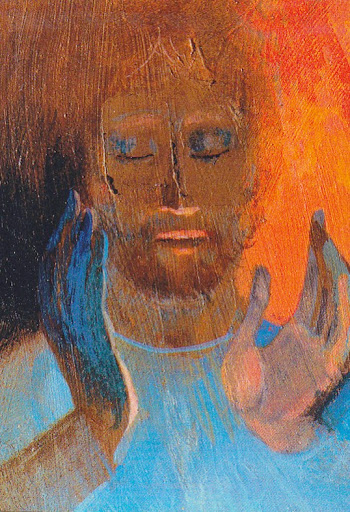

“Of course, this habit of dwelling on the distressing side of human life isn’t new. From the beginning of our civilisation it has been one of the tasks of art to take what is most painful in the human condition and to redeem it in a work of beauty. Art has the ability to redeem life, by finding beauty even in the worst aspect of things. Mantegna’s crucifixion displaying the cruellest and most ugly of deaths achieves a kind of majesty and serenity”

The third flaw I see though is the one that presents the greatest gulf between the beauty that Scruton speaks about and the one that I know: his putting in dualist opposition of the ideal and the particular, of desire and adoration:

“But if human beauty arouses desire how can it have anything to do with the divine? Desire is for the individual, living in this world. It is an urgent passion. Sexual desire presents us with a choice: adoration or appetite? Love or lust? Lust is about taking, but love is about giving.

Lust brings ugliness – the ugliness of human relations in which one person treats another as a disposable instrument. To reach the source of beauty we must overcome lust.

This longing without lust is what we mean today by Platonic love. When we find beauty in a youthful person it is because we glimpse the light of eternity shining in those features from a heavenly source beyond this world. The beautiful human form is an invitation to unite with it spiritually not physically. Our feeling for beauty therefore is a religious and not a sensual emotion.”

Beyond the questionable leaps from desire to sexual desire to lust, Scruton’s thought here too is self-inconsistent: lust leads to ugliness which makes one treat another as an instrument; beauty in youth points to “light of eternity”. To my mind Scruton’s proposal for how to engage with beauty is as objectifying as the sexually-lustful one he decries. In both the case of a source of beauty being turned into an object of one’s pleasure and the case of it being treated as a means for seeking an eternal ideal, that source of beauty is not engaged with for its own sake but is used as a device for satisfying its “consumer”’s ends. And while one can argue about the relative merits of those two ends, their seeking degrades beauty into a mere means.

Scruton’s thought here seems like a polar opposite of the caricature of contemporary art that he battles against, which, however, makes it a caricature too, pitting the beauty of the material and sensory against the beauty of the spiritual and ideal, instead of being open to the union and mutual enrichment of both.

Just to give an example of what an approach of differentiated unity – instead of dualism – looks like when applied to desire, let us consider the way Fr. James Martin, SJ speaks about it:

“[S]adly, desire has a disreputable reputation in many religious circles. When many hear the term, they think of two things: sexual desire or material wants, both of which are often condemned by some religious leaders. The first is one of the greatest gifts from God to humanity; without it the human race would cease to exist! The second is part of our natural desire for a healthy life — desire for food, shelter and clothing. […]

The deep longings of our hearts are our holy desires. Not only desires for physical healing, as Bartimaeus asked for (and as many ask for today) but also the desires for change, for growth, for a fuller life. And our deepest desires, those desires that lead us to become who we are, are God’s desires for us. They are ways that God speaks to you directly, one way that the Creator deals with the creation. They are also the way that God fulfills God’s own dreams for the world, by calling people to certain tasks.”

Such a recognition of good in desire leads to greater appreciation of the entirety of the universe we inhabit rather than to an a priori discarding of either the totality of the material/sensual or spiritual/ideal. In fact it leads to a vision of art like that of Pope Francis who said that “art must discard nothing and no one.”