This is my third attempt at starting a post1 that I have been thinking about intensively all weekend (and that follows a train of thought that I have nursed on and off for years). Why write about it now? Because I believe I have finally understood something that has been staring me in the face for years: the opening line of St. John’s Gospel is a joke!

“Whoa!” I hear you say “Hold it right there!” Before you start crying “Blasphemy!” or “Stone him!,” please, do hear me out.2 I don’t mean to say that it is ridiculous, frivolous, trivial or inconsequential. On the contrary! I believe that I can now see a twist of humor in it that furthermore alludes to complexity that would otherwise have taken tomes upon tomes to try and spell out and that would have been well beyond St. John or the Christians of the first many centuries.

Picture this (imaginary, non-canonical!) scene:

God the Father, Jesus and the Holy Spirit are sitting around a table, chatting (you can imagine that this is what they spoke about in the scene Rublev painted, if you like):

Father: OK, guys, let’s get John started with his Gospel.

Jesus: Dad, can we have him spell out how it all started, and not just open with my birth?

HS: Sure(!), but the maths might be a tad beyond him, don’t you think?

Jesus: I didn’t mean to give him the full recipe, HS! This is not about repeatability and independent verification …

HS: So, were you thinking along the lines of the atemporal – yet dynamic, hyper-dimensional, infinite, partaking in the finite, linear, half-axis of time and being delimited in space? Even if we dumb it down to the level of philosophy, it’s still a tall order (although if anyone can do it, I can!).

Father: Look, HS, Jesus does have a point – we could give them a sense of what is going on, without having to bring Ambrose, Thomas or Albert forward. Surely you can think of some little quip to point them in the right direction.

[A “moment”’s silence later.]

HS: It’s a bit cheeky, but how about this – and I’m just riffing here (plus they’ll have to wait for Ludwig and Martin to start unpacking it) …

Jesus: Get on with it! We may have all eternity, but I’d rather get back to giving Sidd some more hints.

HS: All right, all right! How about John opens with this: “In the beginning was the Word!”

The Father and Jesus look at each other, wide-eyed, exclaim: “Genius!” and the triune bursts out laughing.

The insight I had, while walking to mass on Sunday morning and thinking about Dei Verbum, the Johannine prologue and Descartes’ “cogito,” was the following: Saying “In the beginning was the Word” is like starting a recipe with “knead the dough.” A word cannot possibly be the start: it requires a language, other words, syntax, grammar and speakers and listeners who know how to play the games it facilitates. Saying “In the beginning was the Word” is saying “Look, this is as far back as we can take you, but know that there was lots that came before.” It places at the beginning an innocent-looking entity: a word, yet one that vehemently points beyond itself. To meaning, to reference, to relation, to function, to communication, to a meeting of minds. With a simple sentence, John (with some help), gives a masterclass on the inevitability of the preexisting and the core of Trinitarian relationships, where, like a word, each person points beyond themselves.

“Alright,” you say, “but why call it a joke?” I believe the structure of this sentence is precisely that of all one-liners: the first part (“In the beginning”) prepares you for a certain set of expectations and the second surprises you with something that just does not fit (“the Word,” which cannot possibly be in the beginning :). This is exactly what Kant meant with “Laughter is an effect that arises if a tense expectation is transformed into nothing.” Not wanting to kill humor with explanation, let me leave you with another example of the same comedic form: “Every winter when the first snow fell, I’d run to the front door with excitement, start banging on it and shout: “Mum! Dad! Let me in!”” (Milton Jones).

Realizing the above, I started seeing the Johannine pattern elsewhere too. Descartes, starts with “cogito ergo sum,” in an attempt to draw a line and derive a philosophy from that stake in the ground. Yet, it is a line that carries a lot of baggage beyond itself. My own earlier attempt too, which tries to take the “cogito” a step further by starting with “Language” is nothing but an explicit acknowledgement of such a necessary preexistence and in no way escapes or circumvents it. Unsurprisingly, the account of creation in Genesis uses the word/language mechanism for indicating the process of creation, where matter is spoken into being (“Then God said: Let there be light, and there was light” (Genesis 1:3)). More surprisingly, one of the Hindu creation accounts (the Nasadiya Sukta in the Rigveda) also employs a similar, though not identical, mechanism: “The One breathed windlessly and self-sustaining […] that was the primal seed, born of the mind.” Even the creation account of the Sumerians (The debate between Sheep and Grain, written in the 3rd millennium BC), highlights the role of language in the process: “the great gods, did not even know the names Grain or Sheep.”

What is clear to me from the above is the fundamental role of language in the process of something coming from nothing, which in a sense undermines the idea of a true nothing having preceded the something. With this in mind, the Christian identification of Jesus with “the Word,” which I have been wondering about for years, makes perfect sense. The Father makes himself known to us by speaking his Son, who in turn points back to Him: “Whoever has seen me has seen the Father.” (John 14:9) and then: “The words that I speak to you I do not speak on my own. The Father who dwells in me is doing his works. Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father is in me, or else, believe because of the works themselves.” (John 14:10-11, with a nice hat-tip to orthopraxy).

So, let me finish with a one-liner: “In the beginning was the Word.” 🙂

1 In a previous version I would have taken you through Lemaître, the Planck epoch and the opening lines of the Tanakh, before getting to the Johannine prologue.

2 Thanks to my über–bestie, PM, for his Nihil Obstat and Transferitur (the Imprimatur of the digital age) – much appreciated!

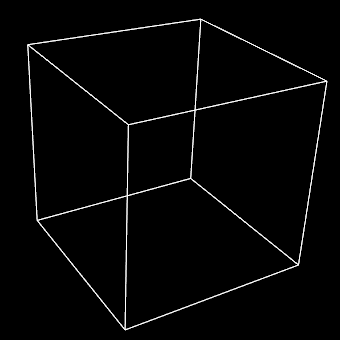

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment:

When you look at the above image, what do you see? Two triangles and five quadrangles, a cube or something else? Now, let’s turn to the following thought experiment: I first came across the “

I first came across the “