Imagine1 sitting on the terrace of a seaside hotel, coolly sipping afternoon drinks, and spotting a yacht heading straight towards you. On beaching the yacht, its sole passenger and captain – armed to the teeth and attempting to communicate with the holiday-makers by signs – persists in the conviction that she has reached a dangerous land, hitherto unknown to civilization, while actually having landed at another of her own homeland’s tourist destinations. You’d certainly feel for her and try to gently steer her in the right direction, but you couldn’t just play along with her delusion.

The above is exactly how I felt (minus the afternoon drink) when I saw a tweet two days ago pointing to “Project Reason” having triumphantly unmasked the shocking contradictions that addle the Bible, with the hope that it would finally bring those religious fanatics to their senses.

🙂

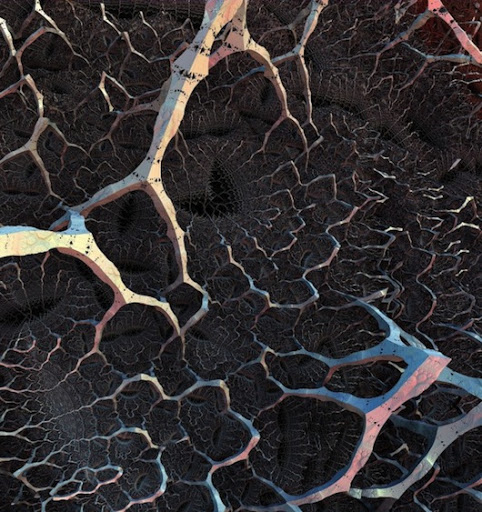

Having scoured the Bible end to end and connected verses that contradict each other, Project Reason have built – and rather beautifully visualized (see above) – a large database of intra-biblical contradictions. I am both grateful to them for this work and certain of the good that reading the Bible has done them (as it does anyone who reads it). What they haven’t done though is in any way question the Bible’s value or present someone who approaches scripture along Dei Verbum lines (i.e., “written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, they have God as their author,” but since they were written by men “[we] must investigate what meaning the sacred writer intended to express and actually expressed in particular circumstances by using contemporary literary forms in accordance with the situation of his own time and culture.”) with any challenge whatsoever.

Project Reason: “Aha! The Bible contains contradictions!”

Me: “Yeah, I know and am profoundly grateful for them!”

Project Reason: “?!” (plus an outsized bead of sweat, emblematic of certain Japanese cartoons, that appears during particularly awkward or embarrassing moments)

Let me try to explain why it is that I consider biblical contradictions a strength and source of comfort rather than a challenge or obstacle. The difficulty I have here is not how to do that, but which of the many parallel reasons to start with.

First, there is the angle that has nothing whatsoever to do with religion and that comes from the impossibility of simultaneously being complete and consistent, proven for formal systems by Kurt Gödel and discussed at some length in a previous post here. A system of axioms (rules) can either be consistent or complete, but not both – if it is consistent it has to be incomplete, while if it is complete it has to be inconsistent. Christians believe that revelation is complete in the person of Jesus, which makes inconsistency in his and the Church’s teachings be no surprise to those of us who have a fondness for formal systems and mathematics. That may sound weird, but it sure as Kurt is not unreasonable or irrational.

Second, Christianity (and Judaism too) is about the relationship with a person – God – not about following rules2 (as much as militant atheists would like to believe so). If anything, the contradictions in Scripture underline the necessity of seeking to personally relate to God, to listen to one’s conscience and to seek to live in every individual and unique moment in a way that is a participation in the life of God. In C. S. Lewis’ words: “Doctrines are not God: they are only a kind of map. But that map is based on the experience of people who really were in touch with God.” To which my bestie ML adds: “We should not mistake a map for the territory it describes. We do not turn to the page picturing the ocean in an atlas and expect our shoes to get wet.”

Third, there is the basic fact that different contexts require different words and actions to move them towards the same goal. When a child is very young (and I am thinking ~2 years) wouldn’t you exaggerate the dangers of them sticking anything into a power socket, while when they are older you can explain to them with greater precision what it is that would be dangerous and what wouldn’t (and introduce the whole topic of electricity, conductivity, etc.)? My favorite example of this type of “contradiction” is the “not with us = against us” versus “not against us = with us” case that Project Reason also picked up on. Here we have Jesus say “Whoever is not with me is against me” (Matthew 12:30) at one point and “For whoever is not against us is for us” (Mark 9:40) at another. A contradiction. Right? No, not really – in the first, Matthean case Jesus is referring to his driving out “demons” and this meaning that him and the demons are in opposition, while in the second, Marcan case Jesus is talking about someone who was driving out demons in his name and who his disciples were jealous of. Instead of being a contradiction, this example is actually fully consistent – Jesus is against demons and those who are also against demons are with him …

Fourth, if you believe that the Scriptures were “written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, [and] have God as their author” (Dei Verbum), then this immediately points to a necessary and vast mismatch in dimensionality between the source (God) and its representation/projection (human words and concepts during the first century AD). Like projections of even just a four-dimensional hypercube into 2D, which give rise to a myriad seemingly unrelated and “contradictory” shapes when considered only in 2D (e.g., how many vertices does this shape have? 4, 7, 16?):3

So too the projections of God’s words into human language necessarily result in apparent inconsistency and contradiction when considered only on the level of human language as opposed to seen as the reductions and conflations they are.

Fifth, to avoid giving the impression of all of the above just being post hoc attempts to explain a feature that the original authors of Scripture did not intend or were not aware of, it is worth noting that contradiction has been a strand in Christian theology that has its origins in the Gospels and that can be traced throughout the last two thousand years (with a recent peak in John Paul II’s thought). This can be seen from Simeon saying to Mary that Jesus “is destined for the fall and rise of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be contradicted” (Luke 2:34) to St. Paul teaching that “For since in the wisdom of God the world did not come to know God through wisdom, it was the will of God through the foolishness of the proclamation [of the cross] to save those who have faith.” (1 Corinthians 1:21).

¡Viva la contradicción!

1 Thanks to G. K. Chesterton for this great image, borrowed from the opening paragraph of Orthodoxy.

2 But, wait! Didn’t your first point assume that Scripture was a formal system and you are now saying that it is not about rules. Aha! A contradiction! – Yes, I know … so? (see the third point).

3 For more detail see a previous post here.